I want to talk about a case that I picked up in the rapid assessment area of my emergency department where geography, as it turned out, was not destiny. It was not as glamourous as a challenging airway or as exciting as a pediatric resuscitation and yet it is one that has stuck with me years later. The patient was old. The patient was weak. The patient was dizzy. It was the end of my shift.

She had been seen at another hospital in recent days, sent home each time with no answer for why she was steadily becoming less able to walk. The patient was frustrated. The family present at the bedside upset and annoyed. In short, the perfect case for POCUS….

As eager as a clinical clerk in July, I went to assess the patient.

The history was brief:

She, an 81-year-old woman with a 2-week history of an increasingly painful lower back, left buttock and hip had become increasingly dependent on her walker for ambulation. The patient recalled that she had presented with similar symptoms the year prior and was at that time diagnosed with a lumbar central disc herniation causing cord compression. She required surgical decompression of her lumbar spine and had been recovering well since. The rest of her history was significant for bilateral knee and hip osteoarthritis, hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Prior to her visit to our ED, the patient had been assessed 10 days earlier at an outside hospital and been diagnosed with an OA flare in the context of normal x-rays.

The exam was not conclusive:

Vital signs were normal with an elevated BMI. There was poorly localized left lower back, hip and groin tenderness without swelling, ecchymosis or obvious deformities. She was unable to flex her hip but had otherwise normal range of motion, power, sensation and deep tendon reflexes. Pulses were strong bilaterally.

I felt I was not further in my understanding of the patient’s condition than before I had assessed her.

“…lumbar central disc herniation causing cord compression…”

“…significant for bilateral knee and hip osteoarthritis…”

“…normal x-rays…”

Was the answer to be found in images of her spine, a hip arthrocentesis? Certainly not more xrays without new or previous trauma…

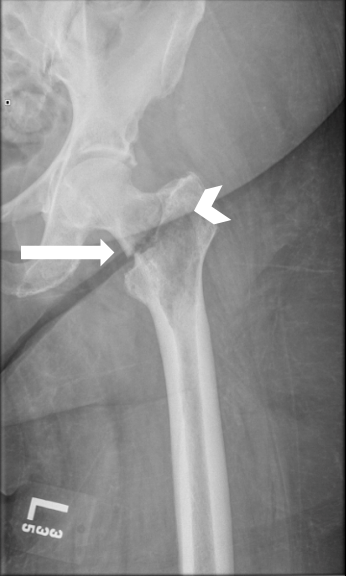

A repeat pelvis X-ray was performed, which did not reveal any obvious pathology. The diagnosis of an osteoarthritis flare was still a strong possibility, but other possibilities remained.

I decided to do what the great ultrasound mentor of our time Dr Melanie Baimel had always taught me..

Put the probe where it hurts.

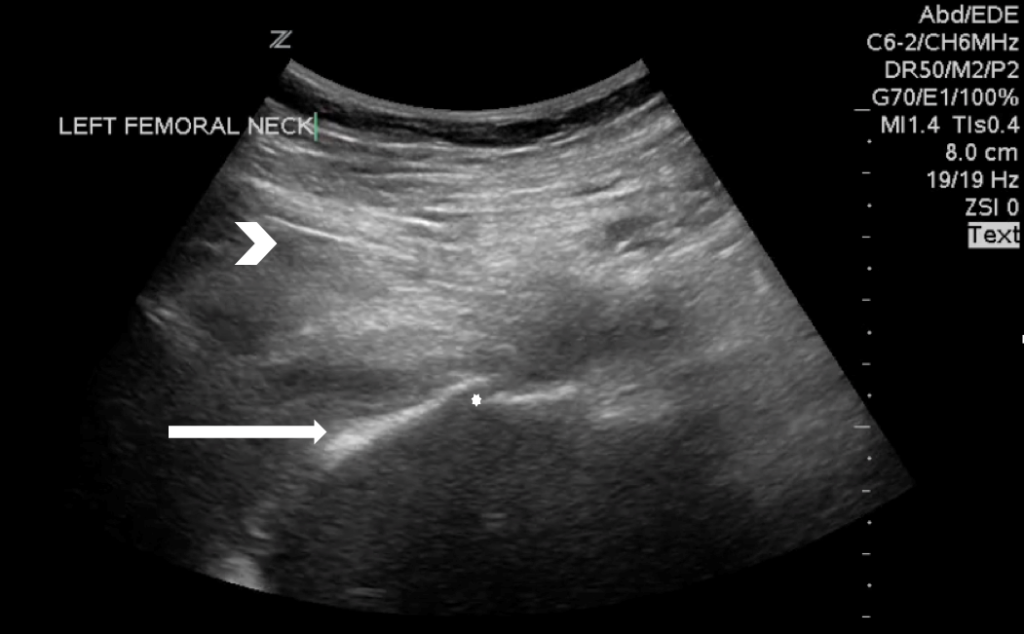

So I did. I placed the probe over the groin and focused on the bony landmark of the femoral head and neck.

Even without the helpful arrow sign, it was quickly apparent that what should have been a single solid line of bone was now two solid lines of bone. And that’s all there is to it. If the patient can point to where it hurts and you can count to two, you can use POCUS to diagnose occult fractures. Because that is what this patient was suffering from. A fractured hip, not present or not seen on her previous visits. I repeated her xray which confirmed the diagnosis.

An underlying radiolucency within the femur was concerning for malignancy. The patient was admitted for open reduction and internal fixation. An inpatient cancer work-up confirmed metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma with metastases to the left femoral neck, right pelvis and bilateral shoulders. The patient began palliative radiation treatment as an inpatient and was discharged in stable condition to an outside rehabilitation facility three weeks later.

POCUS didn’t save a life that day. But it did make an important impact in the trajectory of the patient and reduce the time to her diagnosis significantly. These scans are easy to learn and easy to perform. They are also important skills to have.

POCUS for Hip Fractures

Femur fractures are common in the elderly population and are fraught with downstream complications, morbidity and mortality. (1) Usually, if there is a history of trauma in a frail patient along with physical exam findings suggestive of acute bony injury, plain film imaging is enough to confirm the diagnosis of hip fracture. However, multiple studies have shown that there exists a rate of missed hip fractures on x-ray anywhere from 2-10%. (2,3) Relying solely on a negative plain film report can therefore lead to delayed diagnosis in these patients with an associated increased morbidity. (4–6) Advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly used to reduce these diagnostic false-negatives, with MRI being the gold standard. (7,8) However, MRIs are costly and time consuming, and access to CT is not universally available. (9)

Portable bedside ultrasound (US) has been well evaluated in the assessment of traumatic long bone fractures and found to be useful in time-sensitive situation and more remote settings with sensitivities and specificities ranging from 92.9-100% and 83.3-94%. (10,11) US has also been shown to help with the detection of fractures otherwise difficult to identify on x-ray such as fractures of the hand, sternum and ribs (12–15). Bedside hip ultrasound has been used successfully for the diagnosis and aspiration of effusions as well as dynamic guidance for nerve blocks. (16,17) A study by Safran et al. did show that bedside US could detect otherwise occult traumatic hip fractures with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 65%. (18) The scan is performed by placing a low frequency curvilinear transducer parallel to the long axis of the femur. A high-frequency linear transducer may be used for smaller adults or children. The transducer is then moved cephalad towards the femoral head. A slight rotation towards the umbilicus can be helpful when nearing the joint to visualize the femoral head, neck and shaft. The bones and joint space are evaluated for cortical disruption and effusion. (18,19) Any irregularities should be confirmed by comparing with the unaffected side.

POCUS was able to help reduce the diagnostic uncertainty and help to determine the source of the patient’s pain.

Emergency physicians should consider the use of POCUS for suspected fractures when x-rays are negative and to help to identify the source of poorly localized pain.

REFERENCES

- Kannus P, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Vuori I, Järvinen M. Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone. 1996 Jan;18(1 Suppl):57S–63S.

- Parker MJ. Missed hip fractures. Arch Emerg Med. 1992 Mar;9(1):23–7.

- Dominguez S, Liu P, Roberts C, Mandell M, Richman PB. Prevalence of traumatic hip and pelvic fractures in patients with suspected hip fracture and negative initial standard radiographs–a study of emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Apr;12(4):366–9.

- Pathak G, Parker MJ, Pryor GA. Delayed diagnosis of femoral neck fractures. Injury. 1997 May;28(4):299–301.

- Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth J Can Anesth. 2008 Mar;55(3):146–54.

- Zuckerman JD, Skovron ML, Koval KJ, Aharonoff G, Frankel VH. Postoperative complications and mortality associated with operative delay in older patients who have a fracture of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995 Oct;77(10):1551–6.

- Cannon J, Silvestri S, Munro M. Imaging choices in occult hip fracture. J Emerg Med. 2009 Aug;37(2):144–52.

- Hakkarinen DK, Banh KV, Hendey GW. Magnetic resonance imaging identifies occult hip fractures missed by 64-slice computed tomography. J Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;43(2):303–7.

- Hossain M, Barwick C, Sinha AK, Andrew JG. Is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) necessary to exclude occult hip fracture? Injury. 2007 Oct;38(10):1204–8.

- Marshburn TH, Legome E, Sargsyan A, Li SMJ, Noble VA, Dulchavsky SA, et al. Goal-directed ultrasound in the detection of long-bone fractures. J Trauma. 2004 Aug;57(2):329–32.

- McNeil CR, McManus J, Mehta S. The accuracy of portable ultrasonography to diagnose fractures in an austere environment. Prehospital Emerg Care Off J Natl Assoc EMS Physicians Natl Assoc State EMS Dir. 2009 Mar;13(1):50–2.

- Chan SS-W. Emergency bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of rib fractures. Am J Emerg Med. 2009 Jun;27(5):617–20.

- Lalande É, Guimont C, Émond M, Parent MC, Topping C, Kuimi BLB, et al. Feasibility of emergency department point-of-care ultrasound for rib fracture diagnosis in minor thoracic injury. CJEM. 2017 May;19(3):213–9.

- You JS, Chung YE, Kim D, Park S, Chung SP. Role of sonography in the emergency room to diagnose sternal fractures. J Clin Ultrasound JCU. 2010 Apr;38(3):135–7.

- Oguz AB, Polat O, Eneyli MG, Gulunay B, Eksioglu M, Gurler S. The efficiency of bedside ultrasonography in patients with wrist injury and comparison with other radiological imaging methods: A prospective study. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Jun;35(6):855–9.

- Riddell M, Ospina M, Holroyd-Leduc JM. Use of Femoral Nerve Blocks to Manage Hip Fracture Pain among Older Adults in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. CJEM. 2016 Jul;18(4):245–52.

- Freeman K, Dewitz A, Baker WE. Ultrasound-guided hip arthrocentesis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2007 Jan;25(1):80–6.

- Safran O, Goldman V, Applbaum Y, Milgrom C, Bloom R, Peyser A, et al. Posttraumatic painful hip: sonography as a screening test for occult hip fractures. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med. 2009 Nov;28(11):1447–52.

- Medero Colon R, Chilstrom ML. Diagnosis of an Occult Hip Fracture by Point-of-Care Ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2015 Dec;49(6):916–9.

- Pain all over… - October 12, 2019

- DVT POCUS – Pitfalls of the 2-region technique - May 21, 2018

1 Comment

Thanks for this verry interesting case. At the end of the case if you Can put a link toward a litle vidéo tutorial or a course just to show us the way to examinate the femur it will be a great thing thanks again