A 42 year old man presents with shortness of breath on exertion for three weeks. He was initially diagnosed with asthma by his GP, and had some improvement with salbutamol and fluticasone. However, in the past week or so he feels his puffers are no longer helping. He felt “warm” at home (no documented fever), and his co-worker was recently diagnosed with “double pneumonia.” He is wondering if he needs antibiotics. He has had a mild non-productive cough, and denies chest pain, hemoptysis, and orthopnea/PND.

Past medical history

Remarkable only for mild hypertension. He is on no other medications, and is a nonsmoker.

On exam

Looks well with no increased work of breathing. Vitals: T36.1, HR 108, RR 18, BP 128/66, Sats 96% RA

Heart sounds are normal but there is a mild systolic murmur best heard at the apex. Chest is clear, and the rest of the exam is benign. He has no pedal edema, calf swelling, or calf tenderness.

Investigations

High-sensitivity troponin of 35 (no previous, repeat 32). All other labs are normal.

EKG shows LVH with nonspecific T-wave abnormalities.

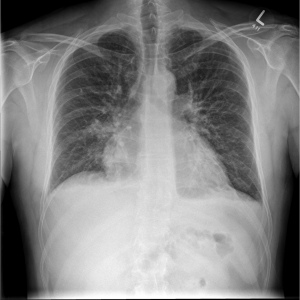

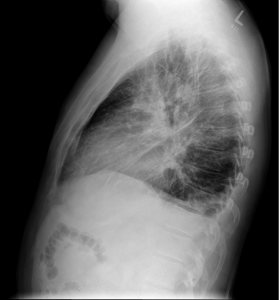

CXR

Under-expanded lungs (which likely accounts for the apparent cardiomegaly/prominence of lung markings), and a focal air space shadowing at the right base (also seen on lateral film) in keeping with infection. Possibly a small amount of pleural fluid.

What would you do? Send him home with antibiotics for pneumonia? Perhaps outpatient f/u for his mild troponin elevation? What about his tachycardia? Is it related to the infectious process? Too much salbutamol? Does he have something more sinister like a PE?

This is where bedside ultrasound can help!

Remember the following assessments for LV function:

- Fractional Shortening – Is the LV squeezing well? E.g., does the diameter of the mid LV decrease by at least 30%?

- Septal Slap – Does the mitral valve “slap” the interventricular septum, or at least come within 1cm of the septum?

- Dilation – Does the LV look about the right size? Remember the LV cavity, measured from endocardium to endocardium in the mid LV, should be less than (about) 5.2cm.

If you answer “NO” to any of these questions, consider the potential for depressed LV function. Remember that these are all extra data points to your clinical exam, as no single US finding can confirm or rule-out a diagnosis.

Here are the patient’s POCUS findings:

Parasternal long view of the heart showing poor LV function

Parasternal short view of the heart showing global hypokinesis of the LV

Apical 4 chamber view of the heart again showing poor LV function

Views of the left and right lung bases, respectively, showing bilateral pleural effusions. Note the multiple B-lines in the lung parenchyma which appear as the patient inspires.

This patient was admitted for workup of cardiomyopathy and new CHF. He improved with furosemide and had a formal echo the next morning which showed a globally depressed LV with an ejection fraction of 30%. He underwent cardiac catheterization the same day to assess for potential ischemic cardiomyopathy. His angiography was normal, and the patient was presumed to have alcohol-induced cardiomyopathy (drinks 3-5 beers per day). He is currently awaiting assessment by the electrophysiology team for consideration of an implanted cardiodefibrillator (ICD) given his poor LV function risk for life-threatening arrhythmias.

Learning Points

Although the history, physical, and CXR can be very helpful in the diagnosis of CHF, ruling OUT the disease is much more difficult. A JAMA meta-analysis [1] found that for CXR even the most useful findings to rule out CHF – absence of cardiomegaly and absence of pulmonary venous congestion – still had relatively poor sensitivity (74% and 54%, respectively). Physical exam findings such as rales, peripheral edema, and jugular venous distention had good specificity but very poor sensitivity (sensitivity 60% or less). History and symptoms such as previous history of CHF, orthopnea, and fatigue/weight gain were likewise reported to have very poor sensitivity (60% or less).

So what can we use to help us diagnose those patients who do not have obvious symptoms or signs of CHF on history, physical exam, or CXR? Studies of bedside ultrasound have shown that medical students [2], emergency medicine residents [3], and staff emergency physicians [4] can learn how to accurately determine LV function. In addition, using focused bedside echocardiography in conjunction with focused lung ultrasound can further help to diagnose the cause of dyspnea [5, 6].

So remember to use your POCUS skills in the patient with undifferentiated or poorly explained dyspnea! Putting cardiac, lung, and IVC scans together can help you diagnose your patient, get them on the right management pathway faster, and potentially save a life.

References

- Wang, C. S., FitzGerald, J. M., Schulzer, M., Mak, E., & Ayas, N. T. (2005). Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure? Jama, 294(15), 1944–1956. doi:10.1001/jama.294.15.1944

- Hope, M. D., la Pena, de, E., Yang, P. C., Liang, D. H., McConnell, M. V., & Rosenthal, D. N. (2003). A visual approach for the accurate determination of echocardiographic left ventricular ejection fraction by medical students. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : Official Publication of the American Society of Echocardiography, 16(8), 824–831. doi:10.1067/S0894-7317(03)00400-0

- Jones, A. E. (2003). Focused Training of Emergency Medicine Residents in Goal-directed Echocardiography: A Prospective Study. Academic Emergency Medicine, 10(10), 1054–1058. doi:10.1197/S1069-6563(03)00346-4

- Randazzo, M. R. (2003). Accuracy of Emergency Physician Assessment of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction and Central Venous Pressure Using Echocardiography. Academic Emergency Medicine, 10(9), 973–977. doi:10.1197/S1069-6563(03)00317-8

- Liteplo, A. S., Marill, K. A., Villen, T., Miller, R. M., Murray, A. F., Croft, P. E., et al. (2009). Emergency Thoracic Ultrasound in the Differentiation of the Etiology of Shortness of Breath (ETUDES): Sonographic B-lines and N-terminal Pro-brain-type Natriuretic Peptide in Diagnosing Congestive Heart Failure. Academic Emergency Medicine, 16(3), 201–210. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00347.x

- Russell, F. M., Ehrman, R. R., Cosby, K., Ansari, A., Tseeng, S., Christain, E., & Bailitz, J. (2015). Diagnosing Acute Heart Failure in Patients With Undifferentiated Dyspnea: A Lung and Cardiac Ultrasound (LuCUS) Protocol. Academic Emergency Medicine, 22(2), 182–191. doi:10.1111/acem.12570

- “Just my asthma” - March 7, 2015