During a recent educational POCUS shift, I was teaching one of our learners how to perform a bedside assessment for DVTs using the well described 2-region compression technique (see video below).

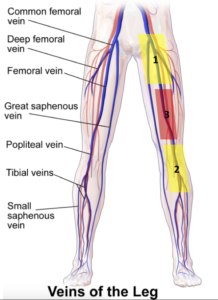

This method focuses on B-mode evaluation of the femoral (region 1) and popliteal (region 2) vasculature and was described by Bernardi et al and found to be equivalent to formal doppler studies at ruling out lower extremity clots in low risk patients. It is also the method primarily taught at POCUS courses and EM residency curricula

It was backed by this evidence and teaching that the learner and I decided to perform a DVT scan of the lower extremities in a young, healthy 28F patient on no medications recently treated for an ankle fracture. The patient had found that since being able to ambulate without her cast a few days earlier, she had noticed worsening calf pain and subjective swelling. On clinical exam, her foot was well perfused with normal pulses, not discoloured and not swollen or edematous. She did have some non-specific tenderness above her ankle. The rest of her clinical assessment was normal.

The scan was easy to perform, and we confidently proclaimed there to be no clot.

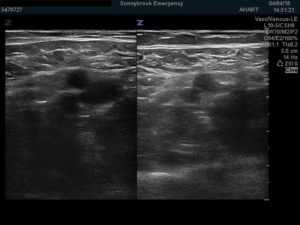

We then compared our findings to the formal duplex ultrasound performed during the same visit.

The technologist’s report was equally confident in it’s proclamation that there in fact was a long and occlusive thrombus of the right femoral vein.

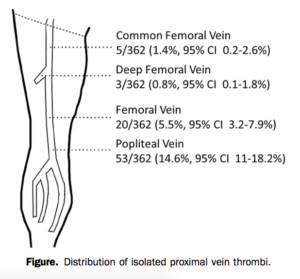

As I was questioning all that I had been taught, and as my learner was beginning to question the abilities of her tutor, I was reminded of a paper published by Adhikari et al. that states that up to 6.3% of clots are isolated to the femoral vein.

While the proximal and distal ends of this vessel are captured in regions 1 and 2, region 3 appears to be a blind spot for the rare isolated femoral vein clot that is not long enough to extend into the dual-region compression technique’s areas of interrogation. It is unclear from studies so far what percentage of clots would lie exclusively in this third region.

So how then to avoid such pitfalls, infrequent though they may seem?

The first reasonable step would be simply to extend the 2-region compression to a 3-region compression with an added look mid-thigh (see video below). It adds seconds to an already quick scan and would help identify those most conspicuous of clots.

More advanced applications are also available to the more intrepid ED sonographers.

These include the use of colour doppler and pulse wave doppler to assess for vascular filling defects, phasicity and augmentation. This along with B-mode compression is what is referred to as a duplex scan.

A filling defect occurs when a thrombus impedes the normal movement of blood through a vessel and thus erases the associated flow generated colour. As we scanned down our patient’s leg, a filling defect became apparent at the mid-thigh region.

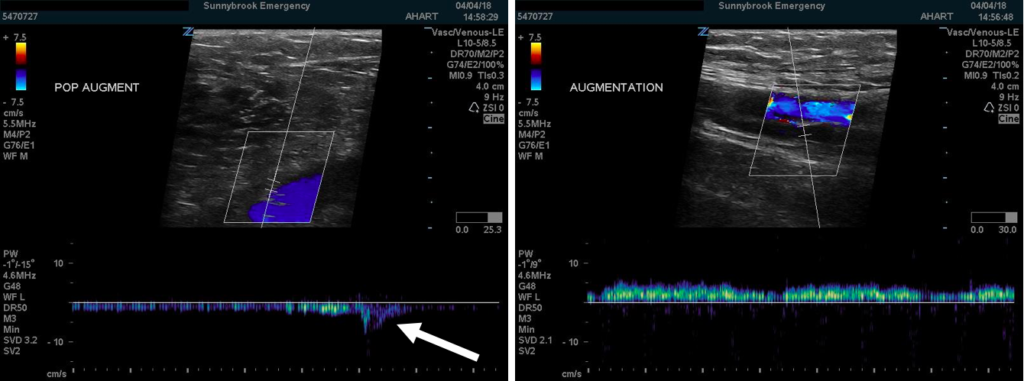

Doppler augmentation is generated by artificially increasing flow through an otherwise low pressure vessel by squeezing the limb distally to the point one is scanning. It is noticeable as an uptick in flow on the doppler tracing. Should a clot exist between the point of manual compression and that of the probe, the augmented signal would be dampened or absent. So while our patient did have augmentation demonstrable in the popliteal region, this was not the case at the femoral region suggesting a clot distal to the femoral region but not to the popliteal region

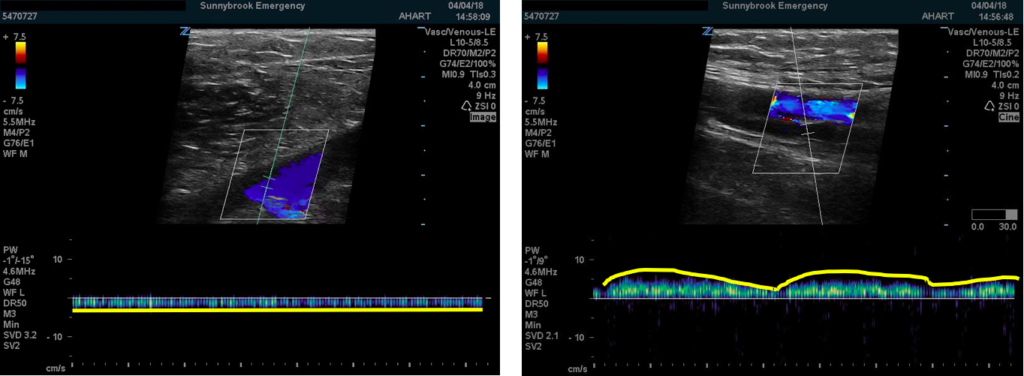

Phasicity is an indirect marker of an occlusive thrombus, this time proximal to the area of interrogation. It relies on variations in blood flow through the venous system generated by respirations. Absence of such flow phasicity suggests a thrombus between the probe and the diaphragm (in this case as in most, proximally). We noted normal phasicity in our patient at the femoral region (suggesting no proximal occlusion) but noted a flat tracing at the popliteal region (suggesting a proximal/downstream clot).

Useful those these adjuncts may be, in the hands of we as EM practitioners who are not able to constantly refine our technique and for who time is always pressed, they may not be the best replacement for clinical judgment. Should your suspicion of DVT remain high despite a negative scan, it is always safest to continue your clinical investigation either with d-dimer testing, in-house doppler studies or simply treating the patient and having them return for definitive imaging at a later time.

- Pain all over… - October 12, 2019

- DVT POCUS – Pitfalls of the 2-region technique - May 21, 2018

1 Comment

Great post Alex. I am going to start adding this. Excellent work.