The FAST exam helped pave the way for Emergency point-of-care ultrasound. Compared to many emergency US applications still in their infancy, the FAST exam has been thoroughly studied, widely implemented, and has proven utility.

… sorry transcranial US…

The FAST has been around since the 1970’s and replaced DPL, it is very sensitive and even more specific. This makes it especially useful as a ‘rule-in’ test allowing expedition of surgery in unstable patients without the delays associated with advanced imaging.

Test Characteristics

Sensitivity: 70-91%

Specificity: 95-100%

RUQ only: 51% sns, 100% spc

Single pelvic view: 68% sns

Improved Outcomes

Time to OR 64% less

Fewer CT scans (OR 0.16)

Fewer days in hospital (27%)

Fewer complications (OR 0.16)

Finally it is teachable, portable and repeatable… not to mention FAST – taking an average of 2-4 minutes to perform

… but nothing is perfect…

Like every test the FAST can steer you wrong, false positives risk unnecessary CT scans, or even surgeries. False negatives can postpone further imaging and delay care. As the amount of US users increase, and no universally agreed upon training standards exist, it is important to ensure the continued accuracy of this critically important skill.

In Part I of this 2-part post I plan to discuss the cardinal features of ‘free fluid’ and how to avoid mistaking pee for blood (among other things).

Part II will follow with a review of the most common sources of false negatives I have encountered in teaching and practice, and how best to avoid them.

LIBERATED LIQUID vs JAILED JUICE

Don’t rely on the blackness – while fresh hemoperitoneum is very hypoechoic, it begins to clot and become echogenic fairly quickly. Not to mention it does nothing to differentiate blood from bile, or aorta from ascites… overall this is an unreliable criteria and shouldn’t be relied on.

I try to remember 4 criteria when I am trying to decide if free fluid is present:

DISSECTING TISSUE PLANES

…. the nook n cranny effect

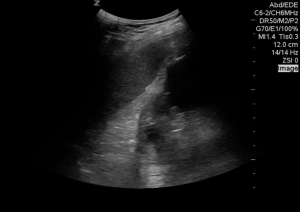

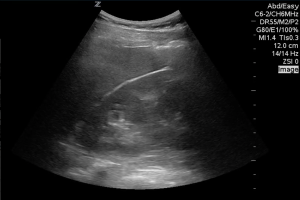

This is a view of a patient’s left upper quadrant, there is a hypoechoic area in the splenorenal interface.

…but is it free fluid?

Unless you have just been taken off the laparoscopy table, there is no open space in the peritoneum, only potential space. Fluid must wedge itself between organs and the parietal/ retro-peritoneum. It doesn’t make sense for it to just disappear or divert from a peritoneal organ, it should follow the contour of the organ and ultimately taper of creating a ‘pointy’ appearance like this:

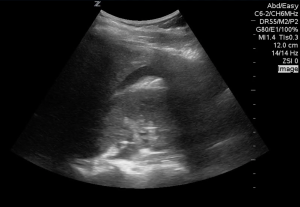

On further investigation the area in the first image was found to be a large renal cyst, this is a short axis view of the same area…

DEPENDENCY

… gravity vs anatomy

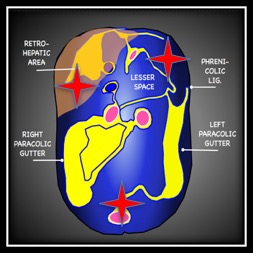

Fluid flows downhill and respects boundaries – it must build up in one area before overflowing to an adjacent area. This seems simple but in the context of the FAST exam it relies on a comfort with somewhat abstract anatomy.

To simplify things, I think of a body lying supine with all of the peritoneal organs removed except for the liver – which must remain as it is tethered to the diaphragm. What you have is the smooth contour of the retroperitoneum and its reflections:

Now we have to consider some other factors, the bladder limits the amount of fluid that can fit in the pelvis so this quickly spills over the pelvic brim.

In order to reach the upper peritoneum fluid from the pelvis must travel along one of the paracolic gutters, the left paracolic gutter is relatively higher than the right and flow is limited by the phrenicolic ligaments so pelvic fluid almost always spreads first to the caudal tip of the liver in the RUQ.

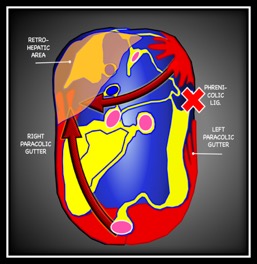

The spleen is the most common source of hemoperitoneum in trauma, and unlike the liver it is small and untethered allowing blood to collect beneath it. This is the reason for emphasizing the ‘6 to 9 o-clock’ view in the LUQ. This is often the first and only place blood can be seen in a serious splenic injury. When explaining this to juniors it can help to reference a coronal slice of a CT. This video shows the superimposition of the US image on the CT. Note how much of this splenic bleed is invisible to the initial view.

It helps understand where the 6-9 o clock position actually is and helps explain why interrogation of this deep recess is so important.

Have a look at this clip of Morison’s pouch.. this hypoechoic line projecting down from the splenorenal interface was mistaken for free fluid.

This ‘fluid’ defies gravity… instead of wedging itself into Morison’s pouch and then moving caudally, it continues medially and goes through the spine. In fact, this is the interplay of shadowing and edge artifact and not free fluid.

UNBOUND BY MEMBRANES

… fluid free from Tyranny

According to textbooks you can mistake almost anything for free fluid… in our experience the most common are the stomach and renal cysts, but anything from the bladder to the heart is possible.

Have a look at this interesting mimic.

Not only does it defy anatomy as in our previous example, but there is a clear membrane surrounding it. Here is what a little further interrogation showed:

This is an aberrant loop of bowel that found its way to Morison’s pouch…

Thankfully they all tip themselves off in the same way…

… they have a wall

Here are some examples:

This is a gallbladder pretending to be fluid – again note the wall (and the sludge!)

This is a stomach pretending to be fluid under the left diaphragm. Note the gastric contents can be almost pure black.

Have a look at another clip, this fluid is free in a sense… but is it in the peritoneum?

This violates two of our rules. First, you can see a membrane all the way around the area. Additionally, the area appears to follow the contour of the kidney and not the liver which violates anatomic boundaries. This was a retroperitoneal bleed in a patient with a Hb of 55 with no blood at all in the abdomen, this patient does not need a laparotomy.

Besides the membrane, watch out for peristalsis, fluid that is fast flowing, or fluid that has a stone in it… and remember it must make sense.

DYNAMICITY

don’t just do something…. stand there

This feels wrong in trauma, but sometimes the right thing for the patient with an equivocal or suspicious negative FAST is to wait. Place them in Trendelendberg, attend to other aspects of management, and then repeat.

Here is the initial RUQ view of a patient who sustained blunt abdominal trauma.

There is a hint of a black strip, granted we can’t see the entire sweep but if this was all there was I would hesitate to commit to surgical intervention.

here is the same patient 10 mintues later…

Now it’s unmistakable, performing serial fasts has shown to improve the overall sensitivity, especially if using only the RUQ view. With pelvic binders and foley catheters a definitive pelvic view is often difficult, but remember space in the pelvis is limited, it will declare itself if it is present.

I hope this provides an easy to remember method of assessing for free fluid,

Remember free fluid MUST be:

… but most of all:

There is a patient behind the image

and a brain attached to the probe!

- Needle Guidance for Procedural Ultrasound - April 9, 2017

- POCUS for Elbow Injuries - February 17, 2017

- Where the Right Upper Quadrant Goes Wrong … pearls and pitfalls in the FAST exam - January 27, 2017

1 Comment

Great post! This is such an important topic, for everyone from beginner scanners to seasoned POCUS users. I love the visuals and awesome scans to illustrate your points. Looking forward to part 2!